A better visual breakdown of the 2023 election results

The usual way electoral results maps are presented can be deceiving, over-emphasising large but sparsely populated rural areas and under-emphasising densely populated ones. Here’s another way to make sense of 2023’s election results.

This analysis was based on the preliminary results. Special votes may change some close results (for example, three electorate seats flipped in the final tally in 2020). The official tally should be announced in about three weeks.

The above map gives us a better impression of how New Zealand votes than the traditional geographic map does alone, as we showed last election. It is easier to see how our communities are balanced, and how they compare to the country as a whole.

Before we break down the results, let’s recap how this hexamap adds to our understanding of the political landscape.

The geographic electorate mapWe can view the results from last night on the geographic map of New Zealand. This is important for seeing who won which electorates.

However, it can be misleading: the large rural electorates are visually emphasised, and the densely-populated urban areas are obscured, even though they all contain the same amount of people. For example, all 31 Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch electorates could comfortably fit into Southland or West Coast-Tasman.

The electorate hexamapInstead, the map below turns each of the 72 electorates into sets of 5 equally-sized hexagons. By presenting the electorates as the same size, we can get a better sense of proportions.

This “hexamap“ reflects the equal power of each electorate, and lets us display the political results more accurately. It retains the general shape of the country, and tries to keep each electorate in a similar position relative to its neighbours.

To help identify the electorates, I’ve labelled the ones with medium-sized cities, and a few of the Auckland electorates. For example, expanding Auckland (due to its large population) pushes Hamilton further south, and Tauranga east; whereas the sprawling West Coast-Tasman shrinks to the corner of the South Island.

Electorate hexamap – candidate voteFirst, we can colour the hexamap to show the winners in each electorate. (We’ll look at the party vote further below.)

The major two parties still won the overwhelming majority of electorates (88% of these seats). However, this election was tied with 1996 for the most electorates won by minor parties (three by the Greens, two by Act and four by Te Pāti Māori). And it was the first time that any third party won more than a single seat outside the Māori electorates.

In total, 48% of candidates (34 out of 71*) won with a plurality (<50% of the vote). This includes 13 of the 22 seats flipped by National, and four of the six seats flipped by the third parties.

*The Port Waikato electorate had no candidate votes counted after a candidate died shortly before the election, which is why that electorate is greyed out.

Electorate hexamap – party vote (total vote)Second, we can show the combined votes of the left (Labour, Greens, and Te Pāti Māori) versus those on the right (National, ACT and NZ First). This analysis excludes the vote share of other third parties outside parliament.

In 2020, 62.3% of the vote was won by parties in government (Labour, Green and NZ First), versus 36.2% to the opposition (National, Act and Te Pāti Māori). This count included the NZ First vote as part of the government due to their 2017 coalition agreement, though they fell below the 5% threshold at the 2020 election.

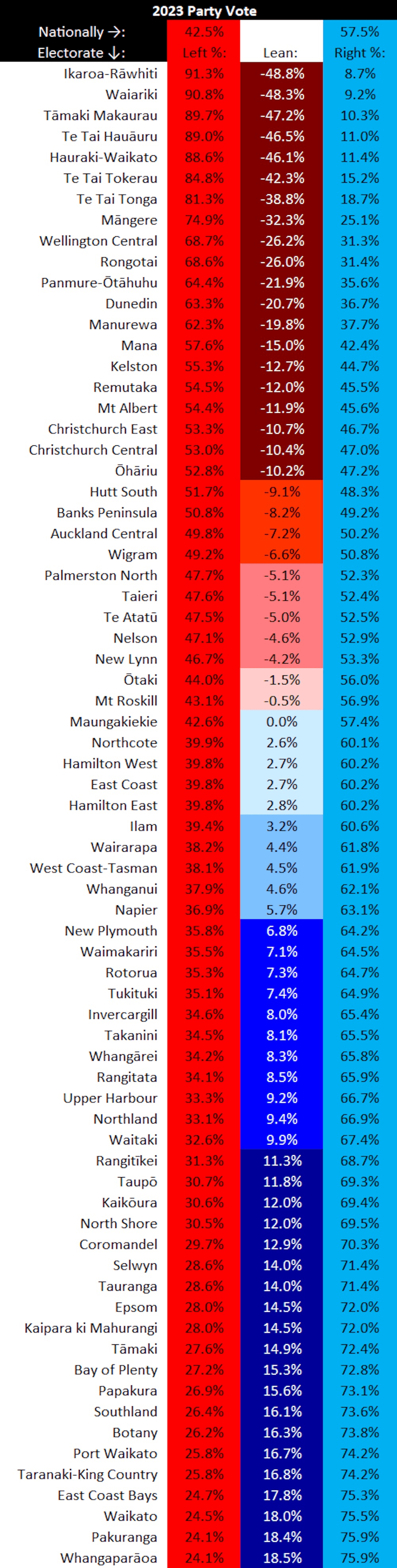

Yesterday, however, the left received 42.5 % while the right got 57.5%, with NZ First returning to parliament. This was a significant shift to the right, with those parties winning more of the collective vote than the left in 50 out of 72 electorates. 2023 also saw the third highest share of the vote for third parties under MMP (with 34% of voters choosing a party other than National or Labour).

Electorate hexamap – party vote (relative lean)Finally, we can also use the hexamp to illustrate the political balance of the country. We do this by comparing the combined votes of the left and the right parties to the country as a whole. It’s a similar picture to 2020 (with most changes simply reflecting shifts among the two blocs, such as NZ First’s votes having exited the coalition government with the left parties after 2020).

Whangaparāoa was the most right-leaning electorate (giving 18.5% more of its votes to parties on the right compared to the country as a whole); Māngere was the most left-leaning general electorate (voting 32.3% to the left), and Ikaroa-Rāwhiti the most left-leaning Māori electorate (48.8% to the left).

Maungakiekie was the electorate that most closely voted like New Zealand as a whole: it gave about the same level of support to left and right parties as the country did overall.

The Spinoff’s political coverage is powered by the generous support of our members. If you value what we do and believe in the importance of independent and freely accessible journalism – tautoko mai, donate today.